Pueblo Chieftain, June 11, 2015

Matt Hildner

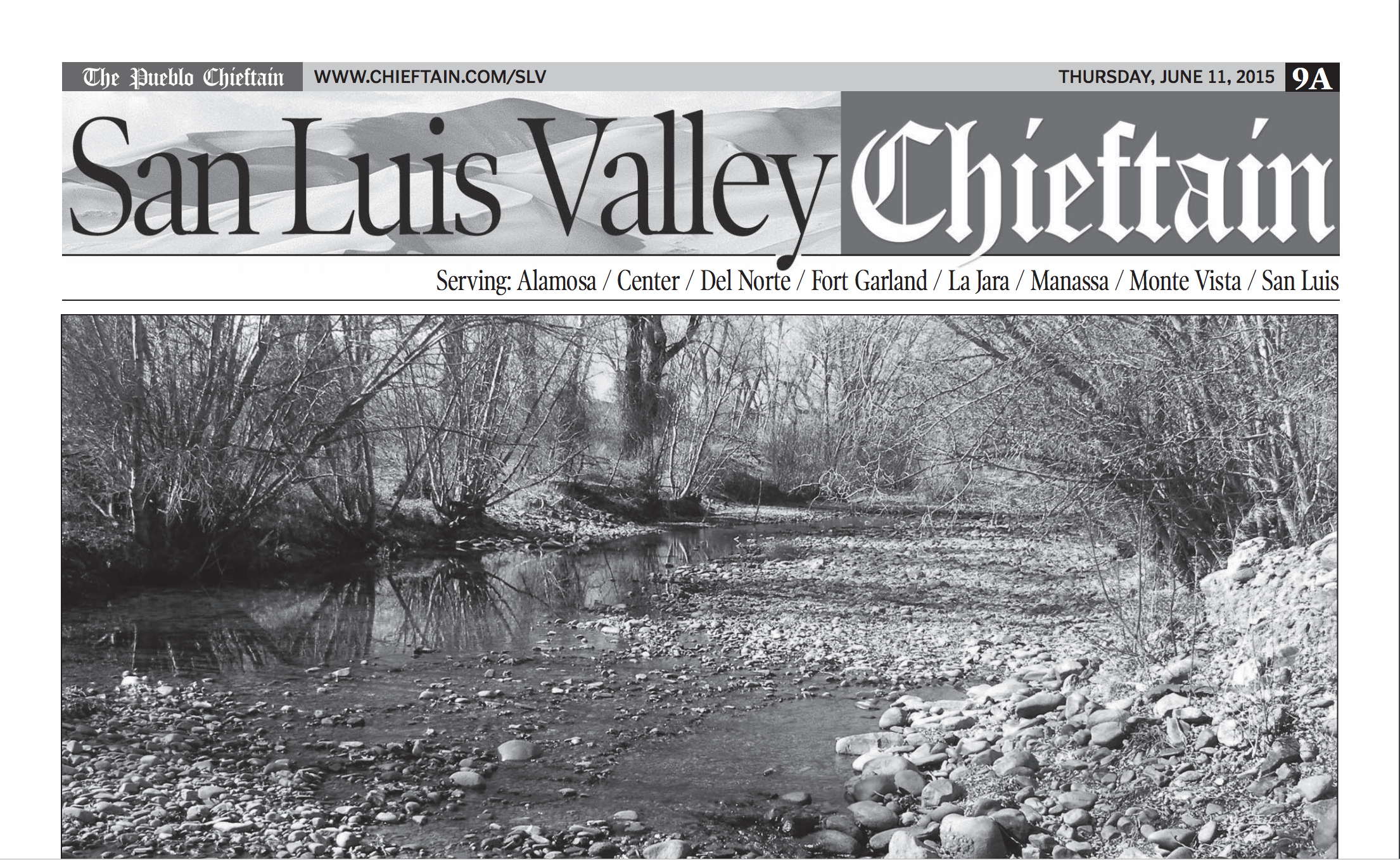

CAPULIN — A river once left for dead by mine-polluted runoff in the southwestern corner of the San Luis Valley is coming back to life.

The Alamosa River, which once included a 17-mile dead-zone thanks to the Summitville gold mine, has seen the return of fish and a local group is seeking to keep it that way by adding to the river’s flows.

“We still have a ways to go but we’ve done a lot,” said Cindy Medina, head of the Alamosa Riverkeepers.

The group is close to finalizing a pair of in-stream water rights in court that could add as much as 550 acre-feet per year to the river below Terrace Reservoir where it runs to the valley floor.

That amount, which translates to roughly180 million gallons, would be stored in the reservoir and released during times of the year when flows are low to nonexistent.

Last week, the Colorado Water Trust honored Medina for her work on the Alamosa with the David Getches Flowing Waters Award.

Key to the in-stream flows, which also would boost groundwater levels in the area, was the cooperation of the Terrace Irrigation Co., which has made storage space available in the reservoir.

Medina also credited landowners along the river like Joe McCann and Rod Reinhart.

“Both of them have been instrumental in this project,” she said.

Reinhart, who grows alfalfa and barley north of Capulin, said he came to understand the importance of riparian habitat and how the in-stream flows could help.

But the importance of how they might help the aquifer also was important given the looming groundwater regulations that might face the valley.

“I think that is huge,” he said. “That’s a big help.”

The need for the restoration on the river and part of the means to do so, stem from the legacy of the Summitville gold mine, which sits at an elevation of 11,500 feet on a tributary.

In 1986, the Summitville Consolidated Mining Company began operation of an open-pit mine on 1,200 acres and used a cyanide formula to extract gold from ore.

A faulty liner meant to contain the cyanide and a company-installed water treatment plant that was far too small ensured high levels of pollutants migrated downstream.

By 1990, fish were gone from the reservoir and the stretch of river above it.

After six years of operation, the company declared bankruptcy and abandoned the site, forcing the Environmental Protection Agency to take over emergency management of the property.

The mine was designated a Superfund site in 1994.

Prosecution of the mining company led to a $28.5 million settlement, $5 million of which was set aside for restoration work in the watershed.

The work of the riverkeepers to increase stream flows is one of the legacies of that funding.

Water quality on the river improved after the Superfund designation, enough so that state wildlife officials began stocking trout in the reservoir in 2007.

In 2011, a permanent treatment plant was built with $19.2 million in federal stimulus funding.

“That improved the water quality significantly,” Medina said.

One year later, the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment lifted restrictions on the consumption of trout in Terrace Reservoir.

Medina is among those who have eaten trout from the reservoir.

“They’ve come out fine,” she said.

But the riverkeepers hope to add more water to the river, by buying water rights from others.

Their goal is to reach 2,000 acre-feet of in-stream flows.

“We’re always looking for more water for the river,” she said.

Scan of the original published article:

Rebirth: Alamosa River, left for dead, is coming back