A new global water report offers a framework for understanding risk, resilience, and why protecting streamflow is critical now more than ever.

Water management has long depended on the assumption that systems will rebound after stress. New research suggests that, in some places, recovery may no longer be guaranteed and that risk may now be accumulating faster than it can be relieved.

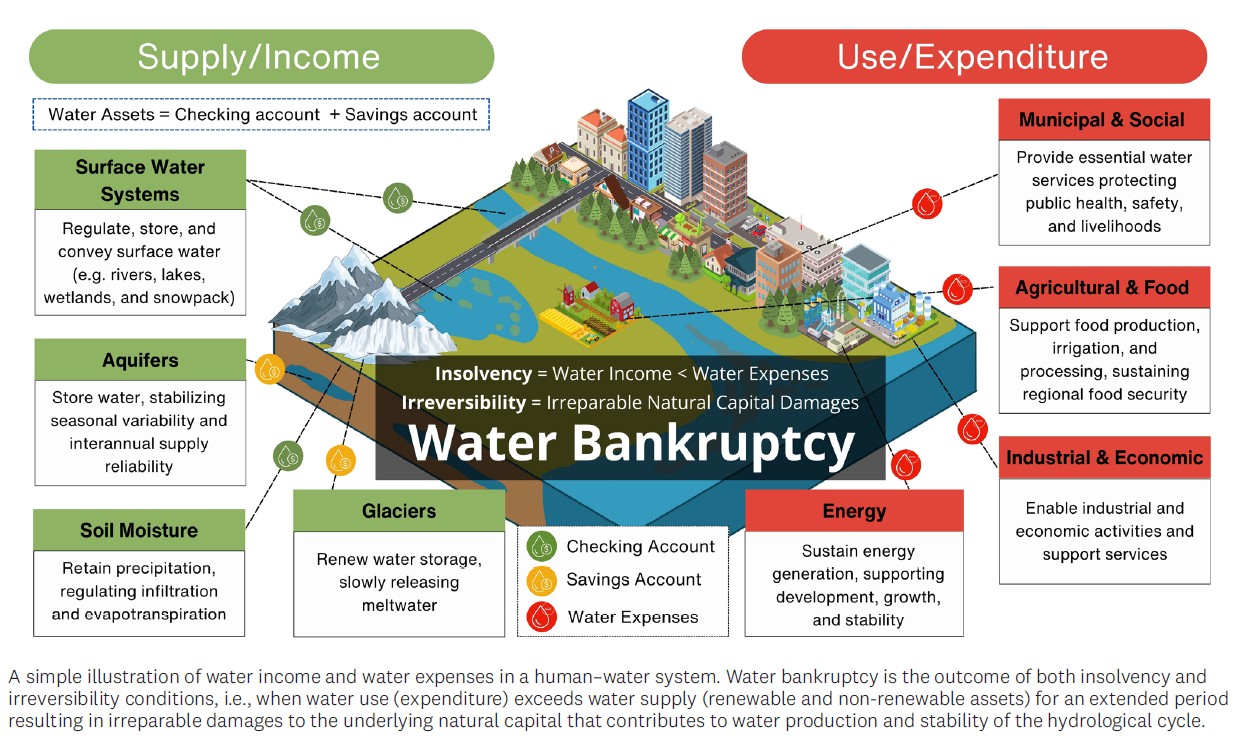

A recent report from the United Nations University Institute for Water, Environment and Health introduces a term for this emerging condition: water bankruptcy. The report argues that many human–water systems are now living beyond their hydrological means. We are drawing not only on the water that is replenished each year through snowpack and rainfall, but also borrowing against long-term ‘savings’ stored in aquifers, glaciers, wetlands, soils, and river ecosystems. Over time, that continual drawdown does more than strain sustainability. It degrades the natural capital that makes water available and stabilizes the hydrologic cycle.

When Recovery Can No Longer Be Assumed

Unlike stress or crisis, which assume eventual recovery, water bankruptcy describes a system that has moved beyond short-term disruption into a condition where loss accumulates faster than it can be repaired.

According to the report, the defining features of water bankruptcy are insolvency and irreversibility. Insolvency describes a condition in which a system can continue to function only by drawing down its remaining assets, rather than living within what can be replenished. Irreversibility refers to the loss of natural capital that cannot be fully restored within realistic planning horizons, even if conditions later improve.

Implicit in this framing is an important insight: water systems falter not only when too much is withdrawn, but when patterns of use become misaligned with the processes that renew and sustain them. When water is consistently removed without regard to its timing, location, or ecological role, the system’s ability to regenerate weakens. The system-scale consequences often appear as instability, loss of function, and shrinking margins for recovery, rather than as immediate shortage. And those consequences affect more than just natural systems; they increase risk for everyone who depends on them.

Colorado Through the Lens of Water Bankruptcy

Across the state, many rivers now experience earlier runoff, longer low-flow seasons, and reduced resilience. In some reaches, the question is no longer whether the river will be stressed in a given year, but whether it will even have enough functional flow, at the right times, to sustain the processes that keep it a river rather than just a delivery canal for downstream consumption.

One of the report’s most useful contributions (and one that might resonate in Colorado) is its emphasis that water availability is not just a quantity problem, but a problem of depleted natural capital. This refers to the physical and ecological conditions that allow water systems to function, replenish, and recover over time. Rivers, aquifers, and ecosystems are not simply “external” values weighed against human needs; they are part of the underlying system that sustains reliable supply. When a river’s ability to do its ecological work is degraded year after year, the system’s capacity to recover shrinks, and management options shrink with it.

In that sense, building resilience into our rivers is a form of system-wide risk management. Streamflow protection creates margin—margin for drought, future pressure, and operational uncertainty—by helping rivers retain enough function to recover through dry periods. Seen this way, adding water to streams is not just an ecological goal but a practical investment in long-term system reliability; it treats rivers as essential natural infrastructure rather than as luxuries. Streamflow protection is capital preservation that helps rivers absorb future stress, recover more quickly, and retain the capacity to respond when conditions change. In a system where recovery can no longer be assumed, that margin is essential. Moreover, protecting streamflow today helps preserve the system’s ability to serve future beneficiaries, not just current ones.

The case for streamflow is often strongest when supply is tight. The costs of losing river function are rarely evenly distributed, and they tend to show up first where flexibility is lowest: among junior users, smaller operators, and rural communities with fewer alternatives. Once function is lost, recovery is uncertain, even if water returns later. Supporting streamflow during critical periods can therefore reduce the need for more disruptive and costly interventions later, helping scarcity be managed through foresight rather than crisis.

Helping Rivers Helps Us All

This is where the Colorado Water Trust’s work fits. For more than two decades, the Water Trust has worked within Colorado’s prior appropriation system to restore and protect streamflow through voluntary, compensated, and collaborative agreements with water users. The aim is not to recreate historical conditions wholesale. Instead, projects are designed to support rivers through critical periods by adding flow where and when it can help streams move through their natural cycle, maintain function during vulnerable seasons, and reduce the risk of long-term system failure.

On the Upper Colorado River, for example, the Water Trust has partnered with agricultural producers and reservoir operators to temporarily reduce diversions or strategically release stored water during late summer and early fall, when stress is highest and recovery windows are narrowest. These agreements do not resolve long-term imbalances in the watershed. What they do is slow the loss of system capacity. They help the river retain enough function to buffer key habitat, move sediment, regulate temperature, and remain connected through critical reaches.

Seen through the lens of water bankruptcy, this work more closely resembles debt management than debt elimination. It helps preserve the natural capital that remains, keeping options open and reducing the risk that today’s imbalances become tomorrow’s irreversible losses.

Streamflow restoration is not a substitute for hard conversations about demand, growth, or allocation. It is a complementary tool for managing risk in the meantime. The point here is not to fatalistically diagnose Colorado’s water system as “bankrupt,” but to ask whether the conditions the report describes are becoming more familiar—and what that implies for how we think about risk, resilience, and responsibility in a future where recovery can no longer be assumed. If rivers and snowpack are the foundations of our water system, then maintaining their ability to function is not a luxury. It is a prerequisite for long-term success.

The report itself emphasizes that responding to water bankruptcy requires more than finding new supplies or engineering around scarcity. It calls for protecting and restoring the natural systems that underpin water availability, managing within ecological limits, and prioritizing actions that preserve long-term system function. In that sense, the most effective responses are those that stabilize capacity before losses become irreversible. For Colorado, that insight reinforces the importance of streamflow protection as a practical resilience strategy, and it’s one that helps maintain the functional integrity of rivers even as pressures increase.

For the Colorado Water Trust, that is the core takeaway. Streamflow restoration and protection are not just about helping rivers survive. They are about building the buffers that make Colorado’s entire water system more resilient and more secure.

By prudently “re-investing” today’s water back into the stream, we can help ensure that future Coloradans will inherit capacity. Not crisis.

Josh Boissevain

Josh Boissevain

Senior Staff Attorney

jboissevain@coloradowatertrust.org

720-570-2897 ext. 6